The decision (first published Tuesday 14 February) is accessible at:

Halton Borough Council, R (On the Application Of) v Road User Charging Adjudicators [2023] EWHC 303 (Admin) (14 February 2023) (opens external website)

– Traffic Penalty Tribunal Chief Adjudicator, Caroline Hamilton, has published a summary of the decision below.

– Stayed Tribunal appeals that were pending the decision will be addressed in due course.

Decision Summary

Introduction

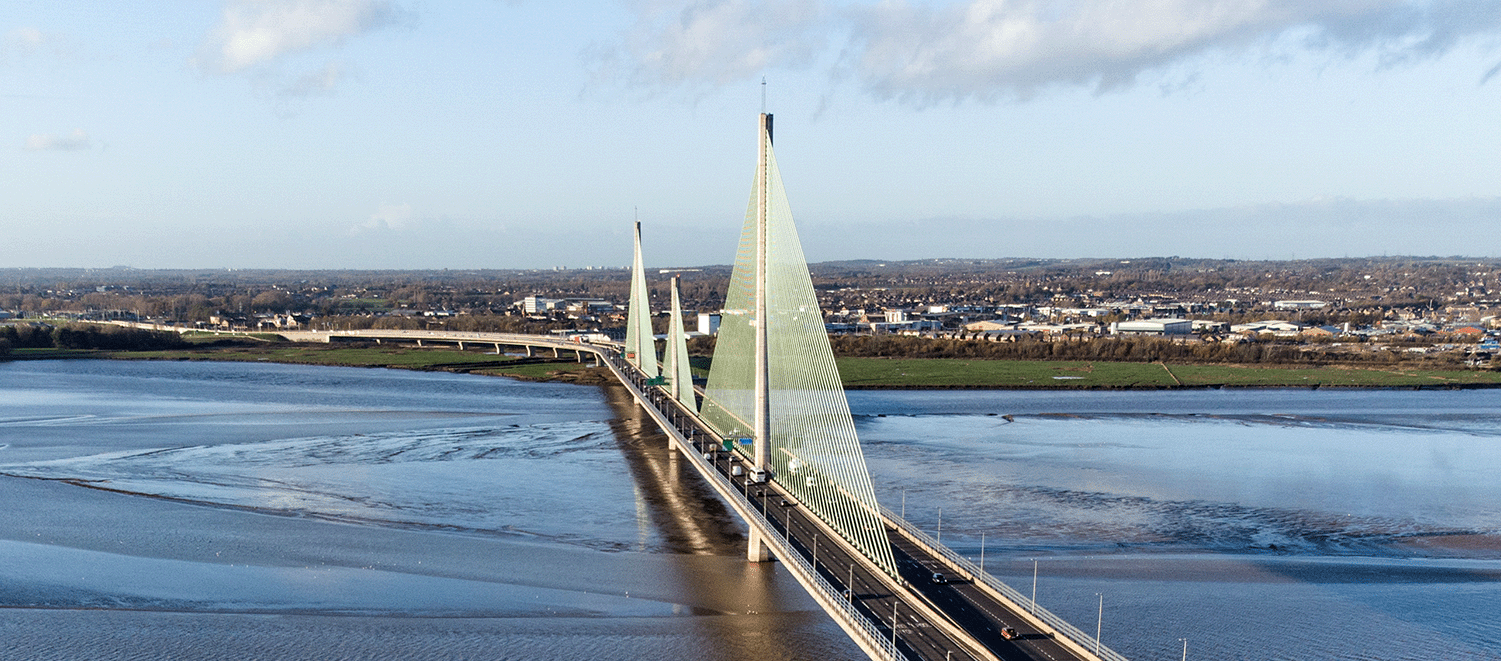

1. The Claimant charging authority (“the Council”) judicially reviewed Traffic Penalty Tribunal road user charging adjudicators’ decisions in test cases which allowed appeals against penalty charge notices (“PCNs”) issued for non-payment of charges under the Road User Charges Scheme applicable to two bridges spanning the Mersey between Runcorn and Widnes (The Mersey Gateway and Silver Jubilee Bridges). The appeals had been allowed on the basis that, in each case, there had been a “procedural impropriety on the part of the charging authority”, a ground of appeal under regulations 8(3)(g) and 11(6) of the Road User Charging Schemes (Penalty Charges, Adjudication and Enforcement) (England) Regulations 2013 (“the Regulations”), by reason of:

(i) unlawful delegation of statutory functions to a third party in relation to consideration of Representations filed under regulation 8(9) (“Representations”)

(ii) unlawful fettering of discretion by the rigid application of criteria set out in “Business Rules”, and

(iii) the provision of misleading information in relation to costs in the Notice of Rejection of Representations (“NoR”).

2. A large number of issues were raised in the claim, and the judgment is long. It usefully summarises and analyses the relevant road user charging scheme. This summary focuses on the three determinative issues, and the core reasoning of the judge (Fordham J) in relation to each.

The temporal jurisdiction of an adjudicator

3. The Council argued that the concept of “procedural impropriety” in regulation 8(3)(g) was confined to matters that occur before the filing of Representations.

4. The judge rejected this argument, concluding that, on the true construction of the Regulations, the concept of “procedural impropriety” included matters that occurred after the filing of Representations under regulation 8(9); and so could constitute a ground upon which an adjudicator could allow an appeal under regulation 11(6) ([37]-[39]). As an alternative route, he also concluded that a failure by the Council to observe the regulation 8(9) duty to consider Representations would in any event constitute a ground of appeal under regulation 8(3)(e) because, under the Regulations, that failure to consider the Representations as required would have the prescribed consequence that the Representations would be deemed to have been accepted (“if it can clearly be shown that there was no consideration of the duly-made representations…” [40(ii)] and see 8(i) below).

Delegation of the regulation 8(9) duty to consider Representations

5. The Council has delegated many of its road user charging functions to a third party contractor. In respect of Representations, these are considered by the contractor, which is required to perform this function by applying a policy (“Business Rules”) that provides for pre-determined decisions in a number of described factual scenarios. A case that does not fit within these scenarios is referred to an “Escalation Panel” of Council employees, who determine whether or not to accept the Representations.

6. The Adjudicators held that it was a “procedural impropriety” for the Council to delegate consideration of Representations under regulation 8(9) to a third-party contractor. The judge found that they were wrong to do so.

7. The judge accepted that, if there had been unlawful delegation, the consequence would have been a breach by the Council of its regulation 8(9) duty, which would be a “procedural impropriety”. However, he held that, under, not section 192 of the Transport Act 2000, or the Road User Charging Scheme Orders, but rather by article 43 of the River Mersey (Mersey Gateway Bridge) Order 2011 as amended (under which the Council was given the power to construct and operate the Silver Jubilee Bridge), the Council as undertaker had a wide power to enter into “concession agreements” in relation to its obligations in relation to “authorised activities”, which included its regulation 8(9) obligation to consider Representations. He did not consider that that construction was undermined by an amendment to the 2011 Order, which restricted the ability of the Council to transfer away its functions as charging authority (see [49]-[65], especially [60]).

Fettering of discretion

8. The judge held that the adjudicators were not entitled to hold that it was a “procedural impropriety” for the Council to adopt a policy, in the form of the Business Rules, to be applied in the determination of regulation 8(9) Representations by caseworkers of the third-party contractor (see [66]-[90]).

(i) The judge held that, while a complete failure to consider representations would be a “procedural impropriety”, anything less would not. So, it would not be a “procedural impropriety” if the caseworker considered Representations with an insufficiently open mind (see [75]).

(ii) In any event, a policy (such as the Business Rules) was not discretion-fettering or (systemically) unlawful by merely providing pre-prepared responses to commonly encountered scenarios where they fit (see [78] and [87]). Where they did not fit, an individual assessment was made by the Evaluation Panel (see [73]).

(iii) Further, on an appeal, the adjudicator could consider the evidence afresh and determine whether a regulation 8(3) ground or compelling reasons had been established (see [89]). This was an important “safety net”.

(iv) Looking at the individual cases, there was no discretion-fettering.

Inaccurate and misleading costs information in the NoRs

9. The judge accepted that the adjudicators were entitled to conclude that the costs information set out in the NoRs was inaccurate and misleading, in that it suggested that costs could be awarded against the Council only if it had acted wholly unreasonably in rejecting Representations, whereas costs could be awarded against the Council in a number of situations (including, e.g., where its conduct in resisting an appeal was wholly unreasonable).

10. However, he held that this did not constitute a “procedural impropriety”, because regulation 10(1)(b) imposed a requirement to include in the NoR only “the nature of an adjudicator’s power to award costs against any person appealing” – which the NoRs did in these cases (see[91]-[95], especially [95(iii)]).